Exploring Lucknow’s Unique Architecture: A Queer Perspective

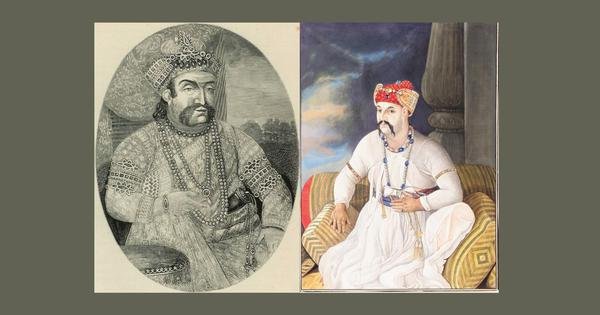

In 1775, Nawab Asaf-ud-Dawla moved Avadh’s capital from Faizabad to Lucknow. He didn’t realize that he and his successors would become rulers the British loved to hate. Historians still debate why Asaf shifted his capital. Some say he wanted to escape his mother, Bahu Begum. Others believe he aimed to build a more prosperous city. Whatever the reason, Lucknow developed a unique culture. Some of this culture lives on in its architecture, thanks to the independent style Asaf established during his 22-year reign.

The End of a Unique Era

This unique style ended in 1856, just before the Uprising of 1857. That year, the East India Company (EIC) took over the kingdom. They used the Doctrine of Lapse, which allowed the British to take over kingdoms that were either misgoverned or had no legitimate heir. Since the Nawab at the time, Wajid Ali Shah, had a son, the British had to prove misgovernance to justify their actions.

A Fresh Look at Nawabi Architecture

A Queer Reading of Nawabi Architecture and the Colonial Archive explores Lucknow’s architecture during this period. It focuses on the reigns of Asif and Wajid, rather than the six nawabs who ruled in between them.

The Queer Influence

Post-Independence Indian historians have provided strong evidence against British claims of misgovernance by the nawabs. Dr. GD Bhatnagar, in his book Awadh Under Wajid Ali Shah, describes Wajid Ali Shah as a complex character. He was a man of pleasure but also a lovable and generous gentleman. He was a voluptuary who never touched wine and never missed his five daily prayers. His literary and artistic attainments set him apart from his contemporaries.

These historians have often overlooked the queer influence on Lucknow’s culture and architecture. Asaf was an accomplished Urdu poet. In some of his work, he reveals his longing for men, which the British found abhorrent. This poetry also highlighted the difference between how most rulers conducted their politics and how a queer ruler might do it.

A Queer City

The book is divided into two sections. The first section discusses methods, and the second section covers the architecture of the buildings. Methods matter because parts of the city were destroyed in the Uprising. Some of the writings of the Nawab’s historians and the Nawabs themselves were also lost. The authors have consulted many archives, including:

- The remaining Lucknow archives

- The written works of Asaf and Wajid

- Archives of the East India Company and the Crown

- Archives of the Government of India

One of the more appealing illustrations is a timeline. It shows Nawabs, British Residents, British Governors General, and various plans and sketches of the city. This offers a bird’s eye view of the city’s history.

The British archives show their contempt for the Nawabs and the queerness of their culture. The British were contemptuous of queers until well into the second half of the 20th century. They imprisoned Oscar Wilde in the 1890s and encouraged Alan Turing’s suicide in the 1960s.

Despite this contempt, the two nawabs continued to hold their political position through acts of transgression, resistance, and sometimes by playing ignorant. Both nawabs furthered an urban cultural environment that rejected macho military standards of politics. They embraced arts as central to shaping the city.

The Shape of the City

The second section covers the actual shape of the city. It details the major works of Asaf and Wajid. Asif’s architectural legacy includes:

- The Machhi Bhavan

- The Daulat Khana

- The Bada Imambada

Wajid’s works include the Qaiserbagh, perhaps the most substantial of the precincts covered.

The descriptions are illustrated in detail. The reconstruction of destroyed parts of these buildings is meticulous and layered, which would appeal to architects. But what appeals to the layman and the historian are the occasional sidelights that liven up the narrative. For example, “The British army was disoriented by the labyrinthine interiors of the zenana but found its flat roof quite navigable because of its continuity.”

Conclusion

For anyone with more than a passing interest in architecture, history, or Lucknow, this book is a small treasure house. It is a guide to the chequered history of one of the most important cities of the British Raj.

Shashi Warrier is a novelist. His latest novel, My Name is Jasmine, was published by Simon and Schuster India in 2025.

A Queer Reading of Nawabi Architecture and the Colonial Archive, Sonal Mithal and Arul Paul, Routledge.